![[object Object],[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/tsza235h/production/fc72f1fc99dd718ae25a9f0b2270c62420b6fb0e-2048x1355.jpg?rect=0%2C102%2C2048%2C1152&w=3840&h=2160&fit=max&auto=format)

Mammoths and Viruses: The Thawing Arctic

Will Industrial Development of the Arctic Trigger New Pandemics?

The Arctic’s permafrost is melting due to the climate crisis, while governments and businesses race to the northern latitudes for natural resources. But as the permafrost thaws, so do the “dormant” viruses and bacteria trapped within it—and we may soon come face-to-face with them. What pathogens are lurking in Russia’s frozen soils, how many people are at risk, and what do mammoths have to do with it? Find out in this joint report by NeMoskva and Arctida.

As soon as the winter chill began to fade, a small band of explorers ventured into the tundra. They were drawn by a recent discovery: remarkably well-preserved mammoth remains. The group split into two—scientists tasked with studying the find, and a film crew set to document the researchers and their extraordinary discovery.

After completing their work amid the Arctic snows, everyone made it back home safely. But soon, a disaster struck: every member of the expedition fell gravely ill with a mysterious infection. The disease was severe and unknown, yet it bore a chilling resemblance to smallpox—fever, back pain, and, most disturbingly, a horrific rash.

It became clear that the source of the infection was the ancient mammoth. The sick were urgently isolated, but it was too late. The disease, soon dubbed “mammoth smallpox,” began spreading rapidly. Hospitals and intensive care units were overwhelmed. A new, deadly pandemic swept across the globe...

It sounds like the opening of another thriller, like “Contagion,” but this isn’t a movie. This is the kind of hypothetical scenario the World Health Organization (WHO) was simulating back in April this year.

For the online exercise “Polaris,” the WHO gathered ministers from 15 countries, including those far from the Arctic—Germany, Ukraine, Somalia, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Each could choose their own strategy to combat the pandemic. Some imposed quarantines, contact tracing, and border closures. Others opted for milder measures. On the second day of the exercise, organizers noted that the differences in their virus containment policies hindered its control.

A new pandemic could become a reality as the climate crisis worsens and the race for natural resources in Arctic territories intensifies. The fictional “mammoth smallpox” scenario was based on real scientific discoveries: the Arctic holds ancient viruses (paleoviruses) that can remain viable for thousands of years. Thawing permafrost could release pathogens unknown to modern medicine.

Encountering unknown viruses is nothing new to humanity. While in recent decades medicine has been able to respond quickly like it did in the case of the coronavirus, in the past, such encounters usually ended tragically for entire peoples.

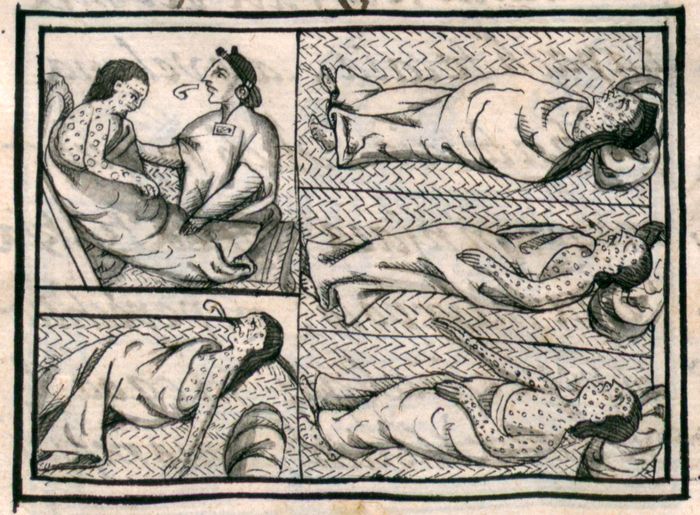

Thus, in 1520-21, smallpox brought by the Spanish to America killed hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of the Aztec Empire inhabitants who had no immunity to the unknown virus. About 20 million people—95 percent of the pre-Columbian indigenous population of the Americas—died from pathogens brought by the Europeans. The same smallpox was a key factor in the extermination of the Khoi San people in South Africa by European colonists in 1713. However, all these diseases were at least known to those who brought them. But what has been lurking in the permafrost for thousands of years—we are yet to find out.

Nothing is eternal…

Scientists studying permafrost call it not “eternal,” as it is called in Russian (вечная мерзлота literally translates as “eternal permafrost”), but “multi-year.” Now it is entirely clear why. The territory with multi-year permafrost—soils that have remained frozen for more than three consecutive years—is vast. It covers a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere and nearly two-thirds of Russia’s territory.

Nikita Tananaev, Candidate of Geographical Sciences and leading researcher at the Melnikov Permafrost Institute of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, told Arctida that permafrost, in one form or another, exists in 28 regions of Russia but occupies a significant area only in nine: Yakutia, Chukotka, Komi, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Magadan Oblast, and Kamchatka Krai.

The depth of permafrost varies across regions—some areas have less than a meter, while in mountainous regions, it can exceed one and a half kilometers. The deepest permafrost can be found in Yakutia. Every summer, the upper layer—also varying by location—thaws.

Now, due to the climate crisis, the air and soil temperatures are rising, causing the permafrost to thaw deeper. Over the past 20 years this has been most noticeable around Vorkuta in the Komi republic, and in Siberia—in the northern Yamal Peninsula, in the areas of Nadym, Urengoy and Novy Urengoy. These are today major oil and gas hubs of Western Siberia. In Nadym, permafrost in the early 2020s was thawing on average 70 centimeters deeper than in the late 1990s, while in Urengoy it was nearly 50 centimeters deeper compared to 2008–2010.

But let’s get back to the mammoths.

Extinct Yet Dangerous?

While the WHO prepares for a potential virus that could emerge from the remains of mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, and other animals extinct for thousands of years preserved in the tundra, real research is underway in Yakutia on a mammoth calf carcass. Yana, discovered in the Verkhoyansk District of the republic last year, has been preserved in the permafrost for over 50,000 years.

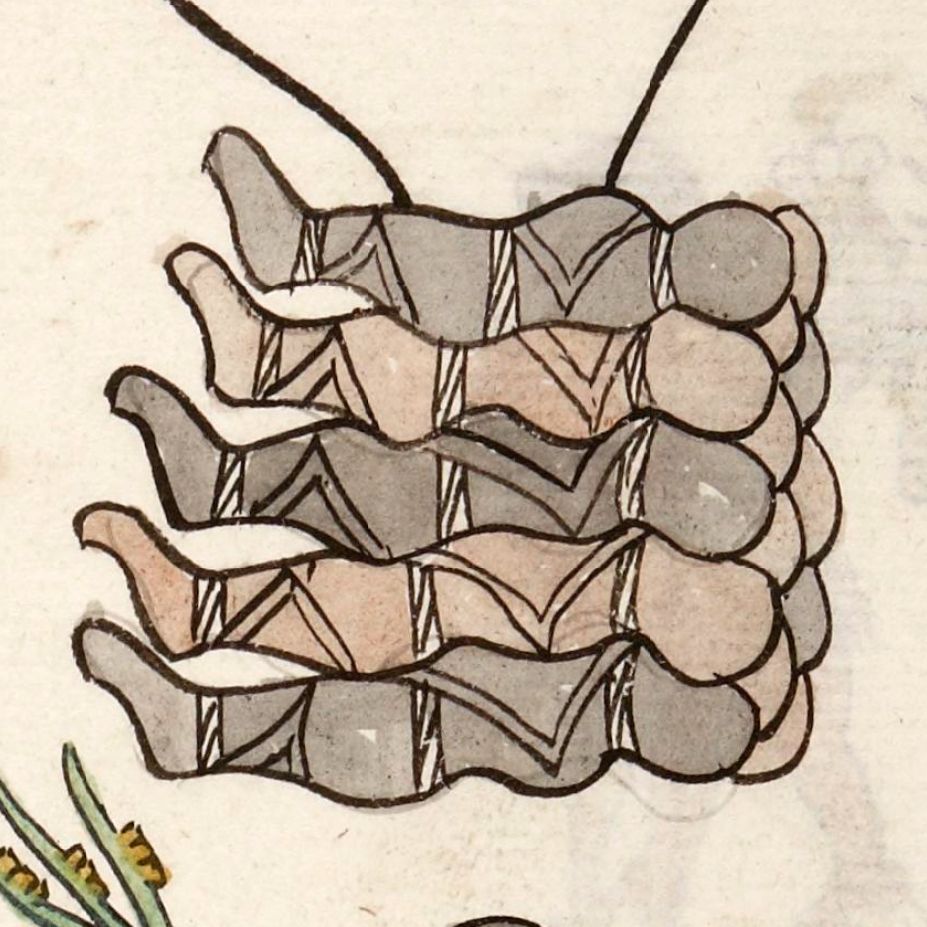

Only seven such well-preserved carcasses have been found worldwide so far. However, scientists say there could be ten million of them in Russian permafrost alone. As the planet warms and the permafrost melts, these remains are becoming increasingly accessible.

In 2014, an international team of scientists extracted a giant virus from the permafrost in Chukotka, dating back 30,000 years and comparable in size to a bacterium. The giant virus has about 500 genes. For comparison, the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic has 13-15 genes.

Later scientists discovered 13 more viruses that had survived in deep permafrost in Siberia and Kamchatka for nearly 50,000 years, confirming their potential danger to humans. Researchers suggest that a “whole world of viruses” is hidden in the permafrost.

Disease Repository

Cold, darkness, and lack of oxygen create ideal conditions for preserving pathogens in deep permafrost layers, some up to a million years old—older than modern humans and even their Neanderthal relatives. This means our immune systems may be unprepared for such an encounter, which is becoming increasingly likely due to permafrost melting and industrial development in the Arctic.

In addition to unknown viruses, thawing permafrost could awaken pathogens of diseases humanity has already encountered but considered eradicated. For example, smallpox, eliminated by 1980 thanks to an effective vaccine, is caused by a virus that can remain infectious for up to 250 years at subzero temperatures. Incidentally, this virus was the "prototype" for the mammoth smallpox in the WHO experiment.

Permafrost preserves not only viruses but also bacteria, including relatives of the pathogens causing anthrax, brucellosis, diarrhea, and staphylococcal and streptococcal infections. Burials of animals and humans who died from deadly infections in the past can be dangerous. We already know how such diseases return: in 2016, extreme heat and the cessation of reindeer vaccination led to an anthrax outbreak in Yamal, the first in the region since the 1940s. The outbreak claimed the life of one child and over two thousand reindeer.

In the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), there are over 200 burial sites of animals that suffered from anthrax. The spores of this pathogen remain viable for decades or even centuries. Yakutia also has cemeteries of smallpox victims from the late 19th century: one such burial was discovered in the early 1990s near the village of Pokhodsk.

Nikita Tananaev points out that anthrax burial sites—like those that led to the 2016 Yamal outbreak—are not always marked, and information about many is missing, raising questions for veterinary service

“Relatives” of modern bacteria sleeping in the tundra currently cause less concern in the scientific community, as a potential epidemic could be relatively quickly controlled with modern antibiotics.

However, a far more catastrophic scenario could arise from plants, animals, or humans encountering a previously unknown pathogen, according to scientists who studied viruses in 2022. New vaccines would be needed, and their development and production would take time. As the COVID-19 pandemic showed, a pathogen can spread across the planet in that time.

About 10 million people live in permafrost regions—roughly equivalent to two St. Petersburgs. Often, there are no people for hundreds of kilometers around. Due to the low population density, Nikita Tananaev remains skeptical about the likelihood of a new pandemic caused by permafrost thawing. Additionally, Arctic regions are isolated, and the chance of a pathogen encountering a human or another carrier is very low

“Findings of ancient animal remains along the banks of rivers flowing through the mountains and tundra plains of Northeast Russia are not uncommon, and anyone can encounter them. However, such findings have not previously posed health threats to people (except for criminal aspects), and it is unlikely that this will happen in the future”.

The scientist believes that the real danger from pathogens already circulating among humans is currently much greater than the “virtual risk of encountering an ancient variety of a killer virus.”

evertheless, “a scenario in which an unknown virus that once infected Neanderthals returns to us, though unlikely, has become a real possibility,” says Jean-Michel Claverie, professor emeritus at the Aix-Marseille University School of Medicine in France, who coined the term “zombie viruses” for these pathogens.

The New Horizons…

The risks are, of course, particularly relevant for the indigenous peoples of the North living on the front lines of the climate crisis, for whom the tundra is their only home. However, warming and permafrost thawing open new opportunities for scientists to study the Arctic, for its development, and for a greater human presence there. Consequently, new opportunities may also arise for viruses.

Besides scientists, mammoths in Russia attract private prospectors, including those illegally exporting their tusks abroad. Such cases have occurred, for example, in Chukotka and Yakutia.

Tananaev notes that after the 2018 ban on the ivory trade in China—its main market—the extraction and export of mammoth remains have become a popular and profitable activity in Russia.

But the Arctic’s treasure trove offers far more than the bones of extinct animals to those willing to explore it. The state and businesses view the Russian North as a strategic resource base and plan to expand the extraction of hydrocarbons, rare earth metals, and other minerals.

Russia’s Arctic Zone Development Strategy until 2035 envisions a significant expansion of economic presence in the Arctic: this includes building new enterprises, terminals, and transport routes, as well as developing mineral deposits and tourism.

“Clearly, the worst exposure scenario is the gathering of a large number of workers around an open pit mining operation, from which permafrost excavated hundreds meters deep would release very ancient and totally unknown human-infecting viruses.”

…and New Responsibilities

Since the threat of pathogens preserved in permafrost is still poorly understood, developing an action plan is only possible after thorough interdisciplinary research. Experts believe it’s necessary to create a state strategy to protect the health of the Arctic population amid the climate crisis. This could include, for example, improving healthcare infrastructure in remote regions so that infected individuals don’t need to be transported to Moscow, which could increase the risk of spreading infections.

It’s also essential to monitor climate factors, such as warming and extreme precipitation, particularly in regions with a history of anthrax outbreaks.

According to Tananaev, the threat posed by permafrost thawing should be considered in the context of the healthcare system’s readiness for an overload that could be more severe than during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While plans for the industrial development of the Arctic are far more ambitious than those for healthcare improvement, Nikita Tananaev offers a different perspective on industrial development in the North:

“The fundamentally better approach today would be to slow down the geological exploration of the Arctic, reduce fossil fuel extraction, and shift focus to more accessible deposits of rare earth minerals in other, more southern regions of Russia (they do exist)”

Maria Ivanova, Arctida’s climate and energy transition analyst, points out that the risks of awakening ancient pathogens in thawing permafrost are barely discussed in Russian society and are insufficiently addressed. Russian legislation on permafrost monitoring also lacks measures specifically aimed at tracking ancient viruses and bacteria.

“The more extensive human presence in the Arctic becomes and the deeper drilling into permafrost goes, the higher the likelihood of encountering bacteria and viruses, which could then be accidentally spread in any direction. If these risks are ignored during industrial expansion into the thawing Arctic, we might find ourselves playing a painfully familiar game of ‘Russian roulette’”