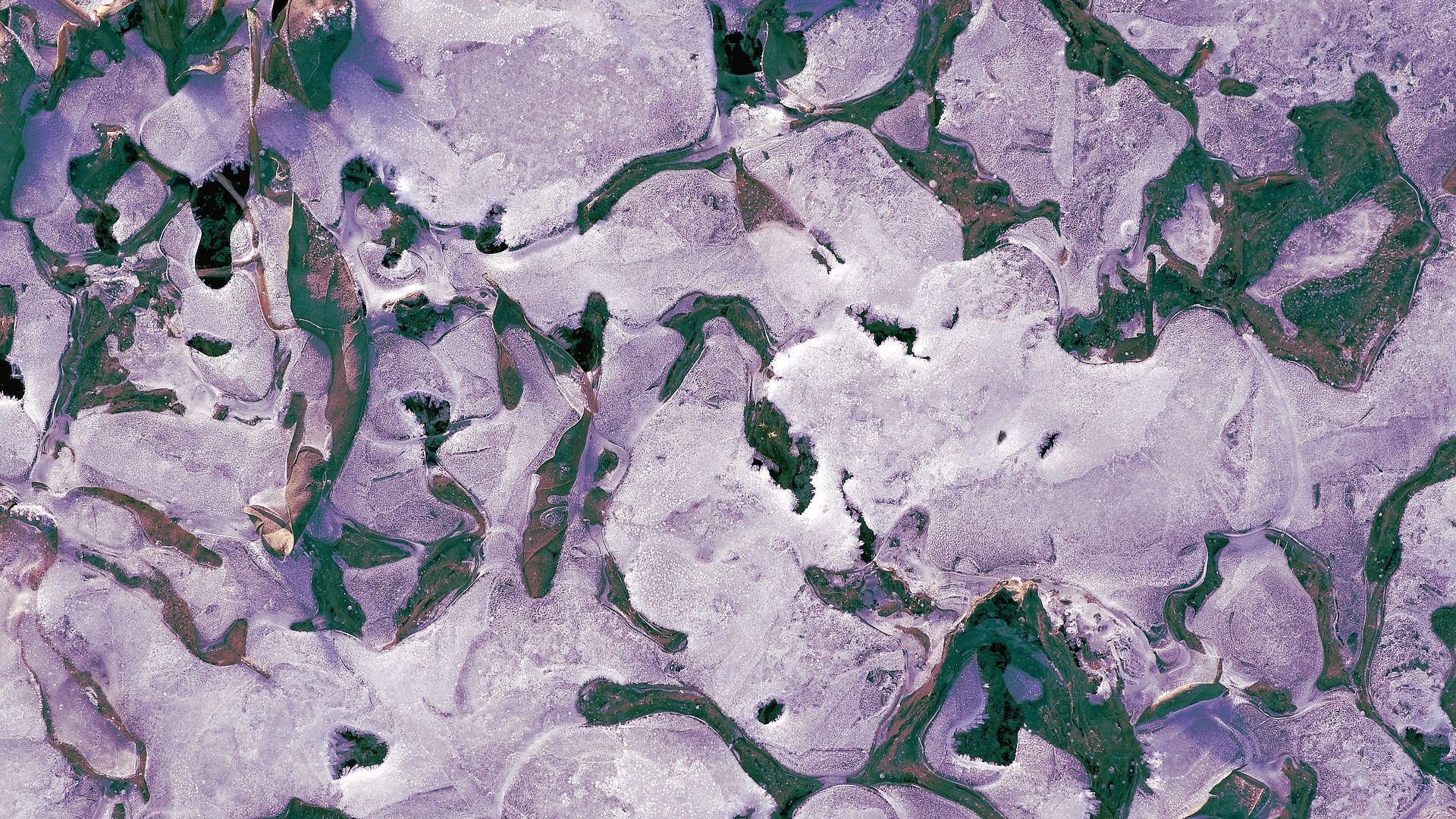

Как спасти мерзлоту: мониторинг против катастроф

Арктика теряет мерзлоту, а вместе с ней — стабильность зданий, трубопроводов и жизни тысяч людей.

В мае 2020 года в Норильске произошла крупнейшая катастрофа с разливом дизельного топлива в заполярной Арктике. Расследование экспертов показало, что причиной стала не только человеческая ошибка, но и отсутствие у компании «Норникель» актуальной информации о реальных масштабах таяния многолетней мерзлоты. С тех пор власти обещают наладить систему мониторинга за тающими грунтами, а тем временем вероятность новых аварий сохраняется. Arctida объясняет, что происходит с теперь уже не «вечной мерзлотой» и почему жители Арктики и бизнес рискуют столкнуться с новыми катастрофами.

Чем грозит таяние мерзлоты жителям и бизнесу

Арктическая зона РФ на две трети стоит на многолетней (вечной) мерзлоте — грунтах, находящихся в замёрзшем состоянии более трёх лет подряд. Однако в результате климатического кризиса из-за антропогенных выбросов парниковых газов мёрзлые почвы начинают оттаивать, что угрожает устойчивости зданий и промышленных объектов. По данным Минвостокразвития, в некоторых арктических посёлках деформировано уже до 50% зданий.

Росгидромет предупреждает: несущая способность свайных фундаментов в этой зоне уже уменьшилась повсеместно на 20-40%, и в ближайшие годы ситуация будет лишь ухудшаться. При этом по санитарным нормам этот показатель не должен опускаться ниже 40%.

В регионе добывают более 80% природного (ископаемого) газа и 17% нефти в России. Деформация почвы под промышленными объектами может привести к экологическим катастрофам, как в Норильске, ущербу экономике и к гибели людей.

Как быстро растает мерзлота в Арктике

В то время как планета продолжила нагреваться и 2023 год стал самым жарким в истории с глобальной температурой на 1,45 °C выше доиндустриального значения, в России зафиксировали повсеместное увеличение глубины протаивания многолетней мерзлоты в тёплый период года, в некоторых местах — на десятки сантиметров по сравнению с 2022 годом. Учёные отмечают устойчивую тенденцию таяния мерзлоты, которое происходит наиболее быстро на Европейском севере, Полярном Урале и в западных районах Западной Сибири.

Масштабы будущих потерь мерзлоты будут зависеть от траектории выбросов парниковых газов, которую человечество выберет в этом веке, — и вызванного ими дальнейшего потепления.

Согласно прогнозу Росгидромета, при умеренных выбросах площадь многолетней мерзлоты в России сократится к середине ХХI века более чем на 20% по сравнению с базовым периодом 1995-2014 гг., а при очень высоких выбросах — почти на 30%. К ****концу ХХI века сокращение составит около 40% и 72% для обоих сценариев соответственно.

Что касается всего мира, то в случае высоких выбросов к концу века на планете может исчезнуть более 90% всей мерзлоты, показало исследование международной группы учёных. Исключение составят нагорья Восточной Сибири, Канадский Арктический архипелаг и самые северные части Гренландии.

Зачем Арктике нужны холодильники

Наряду с борьбой с корневой причиной оттаивания путём сокращения глобальных выбросов парниковых газов, инженеры и учёные разработали меры для снятия симптомов проблемы. Это, например, решения для поддержания инфраструктуры в условиях таяния вечной мерзлоты: выемка льдонасыщенного грунта, охлаждение с помощью термосифонов (пассивных теплообменников), а также проектирование конструкций (например, свай), которые можно регулировать по мере проседания или вздутия грунта.

«Холодильники» в Арктике работают уже сейчас — они в прямом смысле морозят землю, чтобы дома не повело. По словам губернатора Ямала Дмитрия Артюхова, на охлаждающие установки под зданиями ежегодно тратят десятки миллионов рублей.

По прогнозам российских исследователей, к 2050 году на поддержание зданий и сооружений в Арктической зоне придётся потратить около 105 млрд долларов. Больше всего расходов понесут Ямало-Ненецкий автономный округ (ЯНАО) и Республика Саха (Якутия), 52,3 млрд долларов и 21,3 млрд долларов соответственно. Для сравнения, годовые расходы бюджета ЯНАО по текущему курсу составляют почти 4 млрд долларов, а Республики Саха — около 3,5 млрд долларов.

При этом общая стоимость активов на тающей вечной мерзлоте составляет 301,1 млрд долларов. Возможно, в некоторых случаях поддержание инфраструктуры окажется нерентабельным. Но чтобы узнать об этом, нужно как минимум иметь доступ к актуальным данным мониторинга состояния почвы.

Какие проблемы с мониторингом есть сейчас?

Мониторинг должен включать в себя наблюдение за техническим состоянием почвы в различных точках и анализ этих данных для изучения тенденций и прогнозирования. Сегодня наблюдение проводится в некоторых городах и посёлках, на магистральных трубопроводах и других объектах.

Но существующая сеть не покрывает все потенциально опасные точки. А информация с пунктов мониторинга не поступает в единую систему. Это не позволяет экспертам составить достоверную характеристику изменений температуры и свойств грунтов в России.

В свою очередь, международное научное сообщество опасается серьёзных пробелов в понимании процесса глобального изменения климата и, в частности, таяния вечной мерзлоты из-за исключения России из научной кооперации в результате санкций. Так, данные российских мониторинговых станций исключили из международной сети INTERACT(International Network for Terrestrial Research and Monitoring in the Arctic), позволяющей изучать изменения в экосистемах Арктики. Западные страны также поставили на паузу финансирование и научную коллаборацию по проектам, включающим Россию. При этом представитель НАТО заявил в октябре, что Россия «удерживает» климатические данные и со своей стороны.

В 2022 году Канада, Дания, Финляндия, Исландия, Норвегия, Швеция и США также приостановили свою работу в деятельности Арктического совета — межправительственной организации, координирующей деятельность арктических государств в сфере защиты окружающей среды и научных исследований в Арктике. В феврале совет решил возобновить онлайн-встречи рабочих групп.

Впрочем, официальный представитель МИД РФ Мария Захарова заявила, что эта деятельность пока носит «ограниченный характер», и говорить «о полной нормализации работы Арктического совета преждевременно».

Как органы власти обещают усовершенствовать мониторинг

В июле 2023 года был подписан закон о государственном фоновом мониторинге состояния многолетней мерзлоты. В законе впервые прописали понятия «грунт», «вечномёрзлый грунт», «состояние многолетней (вечной) мерзлоты», «деградация вечномёрзлого грунта», «государственный фоновый мониторинг состояния многолетней (вечной) мерзлоты».

В июне 2024 года правительство утвердило Положение о государственном мониторинге многолетней мерзлоты. Согласно этому документу, Росгидромет будет развивать сеть полигонов и станций. Всего планируется создать 140 пунктов наблюдения в зоне вечной мерзлоты. Уже запущены 65 таких пунктов, а до конца года их число должно достичь 78.

Данные со станций обещают передавать информацию в единую систему, а также создавать карты по состоянию почвы. По закону Росгидромет должен предоставлять «текущую и экстренную информацию о деградации вечномёрзлых грунтов» на своём сайте.

Рекомендации экспертов Arctida

Эксперты Арктиды приветствуют подготовку в России нормативный базы для системного мониторинга состояния многолетней мерзлоты, а также открытие новых пунктов наблюдений.

Это демонстрирует, что органы власти, наконец, признали серьёзность проблемы деградации мерзлоты из-за антропогенного изменения климата, о которой общественные организации говорили уже десятки лет.

К сожалению, только крупнейшая в заполярной Арктике катастрофа с разливом топлива в 2020 году стала катализатором разговоров о необходимости эффективного мониторинга мерзлоты. Но сейчас важно, чтобы система государственного мониторинга, который обещают чиновники, способствовала предотвращению новых техногенных катастроф.

Для этого необходимо, чтобы результаты такого мониторинга переходили в конкретные действия по обеспечению безопасного функционирования жилых, промышленных и инфраструктурных объектов в Арктической зоне РФ, включая оценку возможности нового строительства и целесообразности ремонта и поддержания существующих объектов.

Кроме того, важно, чтобы бенефициаром стали не только оперирующие в Арктике компании, но и жители арктических регионов, включая коренные народы — деградация многолетней мерзлоты представляет реальную угрозу для их образа жизни.

Наконец, действия государства должны быть направлены на сокращение выбросов парниковых газов во всех секторах российской экономики. Масштабы таяния мерзлоты будут зависеть в том числе от этого. Если не бороться с первопричиной проблемы, климатический кризис будет только усиливаться, и адаптация превратится в бесконечную гонку на выживание.